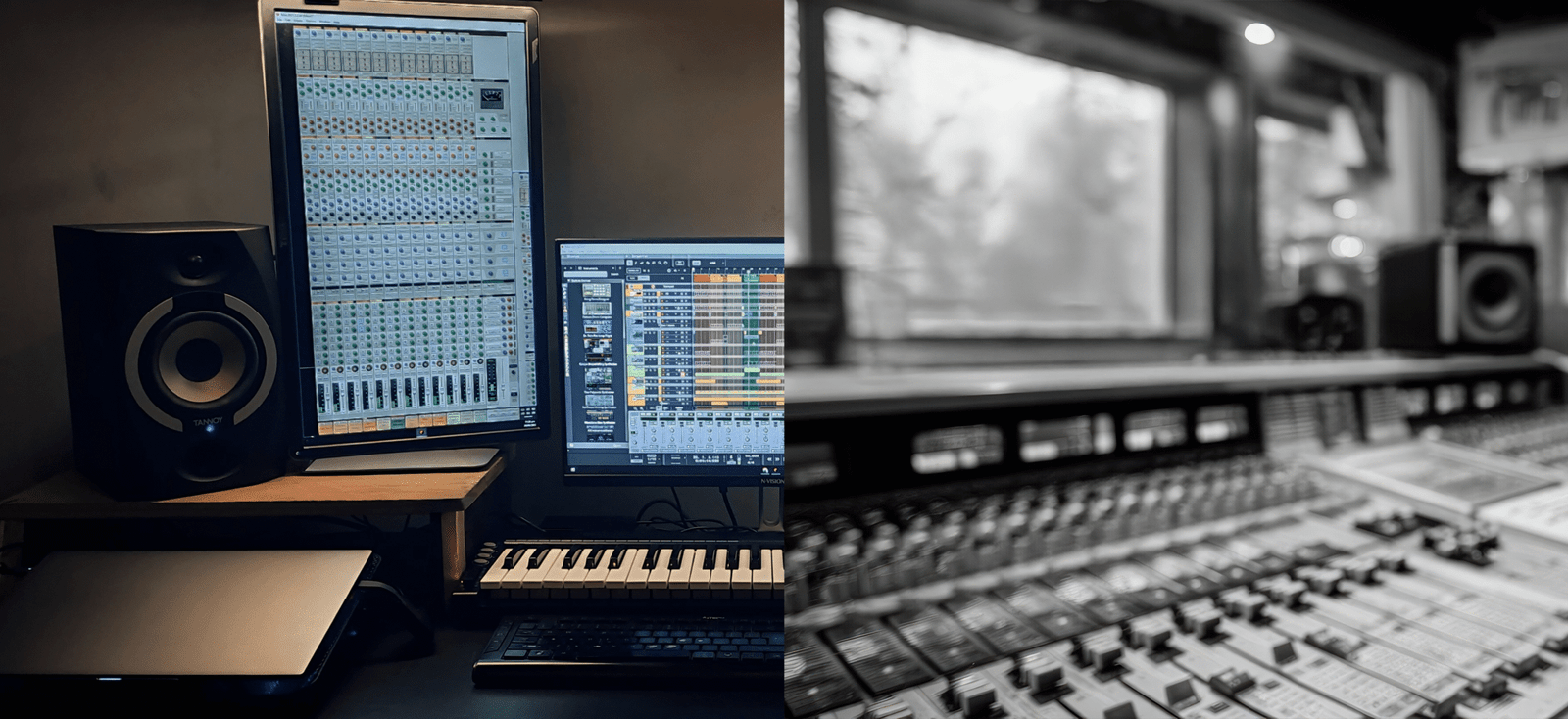

Digital or Tape?

Recording as a musician.

My first recording wasn’t in some polished studio with velvet walls and golden knobs—it was on a humble 4‑track, captured in one take, no overdubs, no safety nets.

We were six souls bound together in sound, each instrument fighting for its own space: four channels swallowed by the drums, keys folded into a bus, vocals clinging to a single track. All of it pressed onto tape inside a cavernous concrete warehouse, where towers of forgotten audio gear stood like silent witnesses.

Later, we tried again in a proper studio, this time with the luxury of an 8‑track analog machine. Three passes, vocals overdubbed last, drums spread across two tracks but mic’d with care. It was cleaner—surgically so. Yet my heart still leans toward that first warehouse take. Not because of fidelity, but because of fire. The performance lived there, raw and unrepeatable. The grit made it sing.

I would go on to chase tape again—analog, digital, multi‑track. The process was always delicate, sometimes maddeningly slow, but efficient in its own way. People romanticize tape, speak of its magic, its warmth. But I’ve learned its truth: fragile, temperamental, utterly dependent on the machines it touches. Compared to today’s seamless digital workflows, it was never convenient. But maybe that was the point.

I think one of the things about recording on tape versus digital, or in the box (computer), is that as a musician/performer, you’re not spoiled with the convenience of technology. Analog always had limitations that had to be worked around. Whether it be with additional hardware or some other ingenious idea, like Sylvia Massy.

Tape forced you to respect the moment. It demanded preparation, discipline, sweat. Before stepping into the studio, we rehearsed until the songs were carved into our bones. We debated EQ curves with our producer, argued over levels, shaped arrangements with the awareness that overdubs were precious, finite. Six members, countless layers, and only so much room to breathe. Every choice mattered.

I would even go as far as to say that the ‘warmth’ that a lot of people are talking about is really about the tightness of performance, and the minor bleeds in the microphones, from one instrument to another, as the real contributory factor to that dimension.

As a mixer, I know bleed is both a gift and a curse. Ten percent is the threshold; beyond that, it’s unworkable. But when captured right, it’s the glue that no plugin can replicate. Even in bigger studios with 24 tracks, limitations loomed. Bouncing tracks was possible, but tedious. Every decision was a negotiation with scarcity.

Not long ago, I found myself back in that mindset, recording a band digitally but with only eight tracks to spare. Four for drums, two for guitars, one for bass, one for vocals. Isolation panels stood guard, but bleed still crept in—minimal, manageable, alive. We tracked it in one take, vocals added after. And when I listened back, I realized: had this been tape, it would’ve sounded almost the same. Ninety‑five percent identical. The spirit was there. (You can read that story here, Haiyan2025)

Today, you can dump all of the creative process without limits, then contain it in a mix, sometimes even polishing it for a performance after the fact.

Two decades on, the rules haven’t vanished—they’ve just been bent, broken, reimagined. Where once preparation was the weapon, today, abundance is the canvas. Today, we can record everything, every idea, every fragment, and sculpt it later like film editors splicing reels. My band does it too: demo, polish, cut, rearrange. It’s a different kind of freedom, but freedom all the same.

Both worlds have their beauty. One shaped by scarcity, the other by excess. One sharpened by discipline, the other expanded by possibility.

And in the end, the only truth that matters is this: if it sounds good, if it feels good, then it is good.